I (and I hope many of you) care deeply about Israel and see it as central to my Jewish identity. When I speak to Jewish adults my age and younger (I am 51) I do not find that to be the norm. I imagine there are many reasons for ambivalence toward Israel by Jews. I suspect one of them is battle fatigue. Too many fights. Between Arab nations and Israelis. Between Israeli Arabs and Jews. Between Palestinians and Israelis. Between Jews and Jews. For some, I suspect it has to do with actions or inactions of Israeli governments, settlers or protesters. (Trying to allow for all political approaches, but probably failing.) And some have just stopped paying attention because they are focused on things closer to home.

In any case, I agree with Gordis. Let's dream about what the Jewish state can be. As Jews living Chutz l'aretz (outside of the land of Israel), let's re-engage and become part of the process. And let's figure out what that means, both to us and to Israelis. After all, if you will it, it is no dream.

Click here to read the original posting and comment on Daniel Gordis' page.

-Ira

Time to Change the Israel Conversation

Posted by Daniel Gordis on June 21, 2013 | 10 responses

Reasonable minds can differ as to whether saying publicly that the two-state solution is dead is healthy for Israel’s standing in the international community, especially at this delicate moment when US Secretary of State John Kerry is amassing frequent flyer miles as he seeks, as have many before him, to get the process unstuck. But reasonable minds should agree – though they will not – that Bennett is right. Even were there no Israeli resistance to the idea of the two-state solution, longstanding Palestinian incalcitrance would doom the project anyway.

The world will take much more note of Bennett’s two-minute remarks than it will of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas’s longstanding refusal to negotiate. When US President Barack Obama pressured Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu into a building freeze that lasted for 10 months in 2010, Abbas refused to come to the table.

Bennett may be right, and he may be wrong. More likely than not, the conflict will muddle along towards some slightly altered reality over the course of many years without the fanfare of a “deal” signed on the White House lawn. Yet though all this will undoubtedly leave much of the Jewish world – in Israel, America and beyond – in a fit of desperate hand-wringing, it should actually come as a relief, and as the harbinger of a significant new Jewish opportunity.

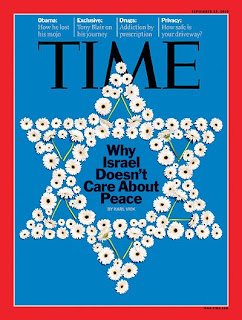

Before us now lies an opportunity to have, at long last, a renewed conversation about why the Jews need a state and the values on which is ought to be based. For far too long, 90 percent of Jewish conversations about Israel have been about Israel’s enemies. Eavesdrop at almost any Shabbat table in New York or Los Angeles, Sydney or Melbourne, London or Paris, and the conversation about Israel is almost invariably a conversation about the Palestinians, or Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, or Iran’s nuclear ambitions. We discuss, ad nauseum, how to preserve the Jewish state, without ever asking ourselves why it matters in the first place.

If every comment about Israel is really about Gaza or Syria or nuclear weapons, what’s the point? THAT IS why Bennett’s remarks actually present an opportunity, even to those who wish matters were different. If there is no “deal” to be had, then there is really little point talking about it. What we can – and should – be speaking about is why the Jewish state matters in the first place.

Ironically, we now have the opportunity to initiate a conversation that instead of dividing us to the point of not being able to speak to each other, can actually unite us in a shared enterprise. What religious and secular, Left and Right, young and old can almost certainly agree on is that if we are to have a Jewish state, its society and values ought to be a reflection of the ideas and values that the Jewish people has long held dear.

But what are those values? What does the Jewish tradition have to say about balancing our need to welcome refugees who are fleeing genocide with our obligation to protect the safety of our own citizens on the streets of Tel Aviv? How do we raise a generation of young Israelis who will remain willing to risk everything to defend the Jewish state, yet who do not hate Arabs, despite the fact that we are intermittently at war with the Arab world?

How do we balance the need to let 1,000 Jewish flowers bloom, and let Jews pray where and how they wish to pray, and teach their children what they believe they need to know, and still maintain – or create – a sufficiently cohesive public square that makes Israel not an accident of different people sharing the cities, but a meaningful collective enterprise? Conversations such as these would get us to open both and Western books. They would invite the input of secular along with religious, of progressives along with conservatives, for Jewish ideas are not the sole province of any one segment of the Jewish world.

Conversations of this sort would remind us all that the business the Jews have been in for the past several millennia is the business of ideas – imagining a world in which human life flourishes, and trying to then make that world real.

It’s time for a change. It’s time to prove Rousseau right, and to remind ourselves – and a listening world – that the Jewish conversation is actually much deeper and richer than that. Ironically, being liberated from any hope that peace is around the corner may actually make possible a much more important and enduring conversation.